The Auditorium Theatre is the result of collaboration between civic leaders who envisioned a building that might make opera and the arts accessible to people in every income bracket. This building helped to bring fine arts to the citizens of Chicago and establish the city as a center for “democratic” cultural amenities.

CHICAGO HEARTS THE ARTS

The Auditorium Building is an example of what can happen when business leaders and the artistic community work together to create functional, aesthetic mixed-use architecture. The developer, Ferdinand Wythe Peck, was committed to bolstering the state of the arts in Chicago. That was tricky business in a time of high tensions after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and not long after the Haymarket Affair. But after organizing a successful opera festival, Peck realized there was an appetite for the arts in the city and he was intent on making them more accessible.

In order to subsidize the cost of a theater, he decided to include an income-generating luxury hotel and business offices. The idea of a mixed-use structure was still a fairly new idea. He planned for profits from the hotel and offices to help keep ticket prices low.

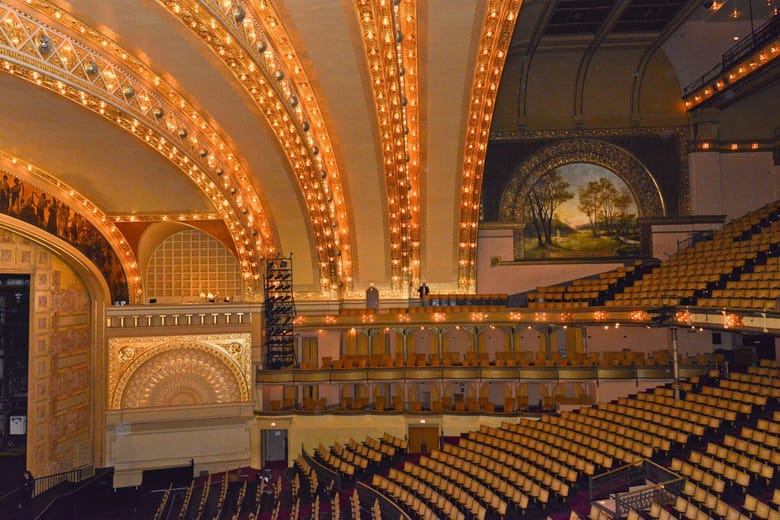

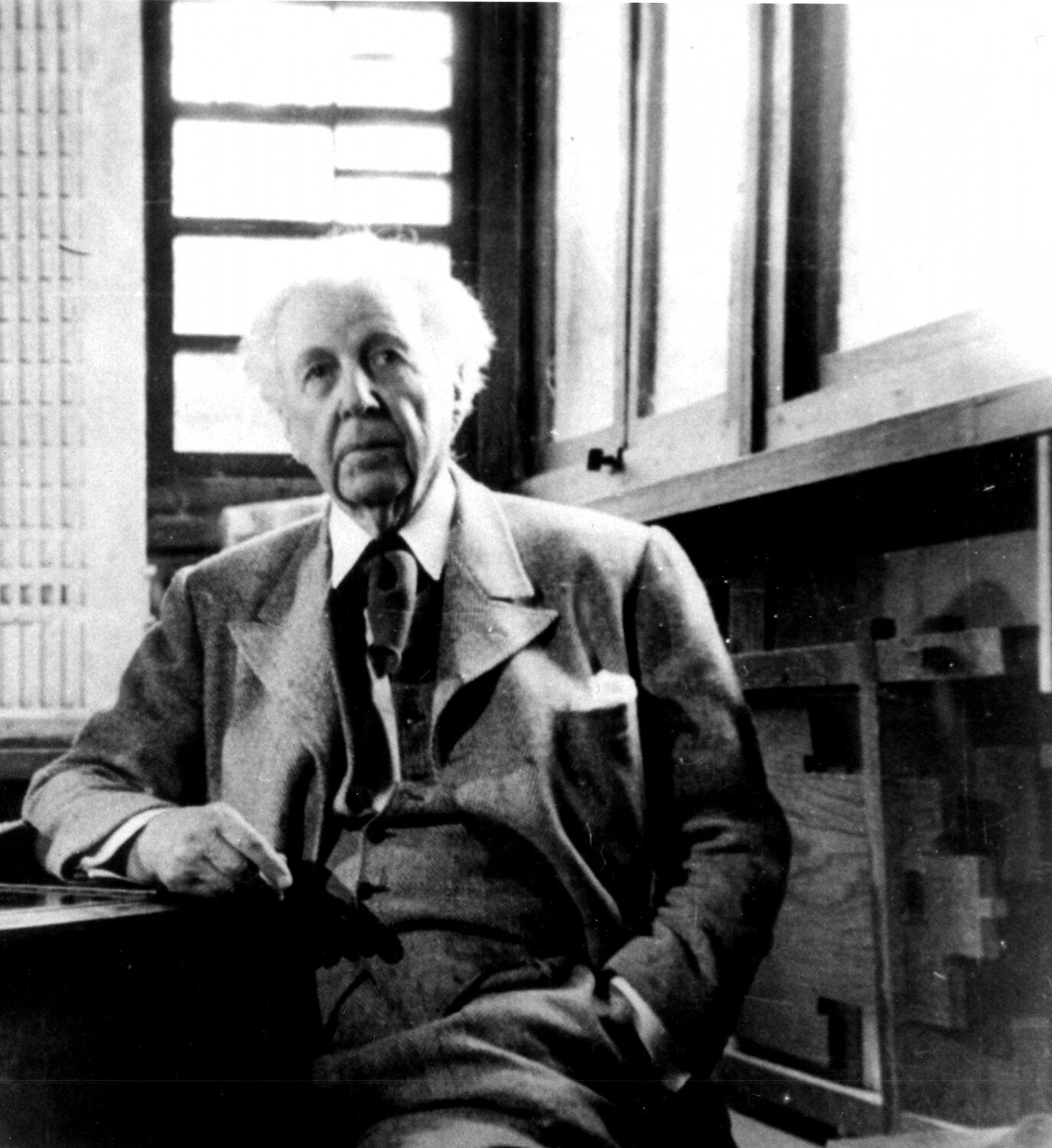

Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan were commissioned to bring this lofty project to life. A young Frank Lloyd Wright was hired as an office draftsman and in the process of working on the massive project, he learned a great deal from Sullivan about the use of organic ornamentation. On the exterior, Sullivan emphasized both massing and the rhythm of repetitive window patterns, using load-bearing stone walls on the perimeter of various textures and colors. The building had separate entrances for theater, office building and hotel. Highly influenced by H.H. Richardson’s Marshall Field Wholesale Store, Sullivan included the use of monochromatic rusticated stone. Meanwhile, the theater and hotel interiors provided an outlet for his genius organic ornamentation.

Adler addressed several engineering challenges. His acoustical design for the theater—in an era before scientific acoustical calculations—is a masterpiece of sound. He developed a foundation substantial enough to support the 16-story tower originally planned for the building. However, after the foundation was in place, Peck requested two extra floors on the tower and the architects complied. The additional two stories caused excessive settlement under the tower, proving Adler's original calculations correct. A banquet hall was also added late in the construction. Adler carried its load on giant iron trusses above the vaulted roof of the theater.

When completed, the Auditorium was the largest, tallest, priciest and heaviest building of its time. It was not only an enormous civic achievement but also a symbol of the city’s success and emergence as a cultural center. The Auditorium’s innovative engineering and design brought international recognition to the firm.

THE BEST LAID PLANS...

Peck’s vision was difficult to fulfill. The hotel and offices could not financially support the theater. In the 1940s, the Auditorium was taken over by the City of Chicago and used as a World War II officers’ center. By 1945, the space had deteriorated, suffering significant damage to Sullivan’s plaster ornamentation. To prevent it from being demolished, Roosevelt University acquired the building but lacked the funds to restore it until 1963 when an Auditorium Theatre Council was formed to raise money for its restoration. Under the direction of architect Harry Weese, the theater was beautifully restored and reopened in 1967.

Did you know?

The theater featured many technological advancements for its time, including the display of 3,500 bare carbon filament light bulbs. Such bulbs had been seen publicly for the first time in 1879.

Did you know?

Peck’s vision for the theater was to create a space that was democratic, where the best seats were not reserved for the wealthiest patrons. Box seats were relocated to the sides, with an expansive main floor and generous balconies that offered optimal sightlines to the general public.

Did you know?

Each patron who arrived for a performance was led through the small, dark entranceway into the theater. The entrance was “compressed” by low ceilings such that when patrons emerged, the impact of “expanding” into the towering six-story auditorium, with its grand gilded arches and glittering ceiling, would be all the more dramatic.