Adler and Sullivan

Chicago Stock Exchange Building, early 20th century.

Wainwright Building, 7th Street and Chestnut Street, St. Louis, MO.

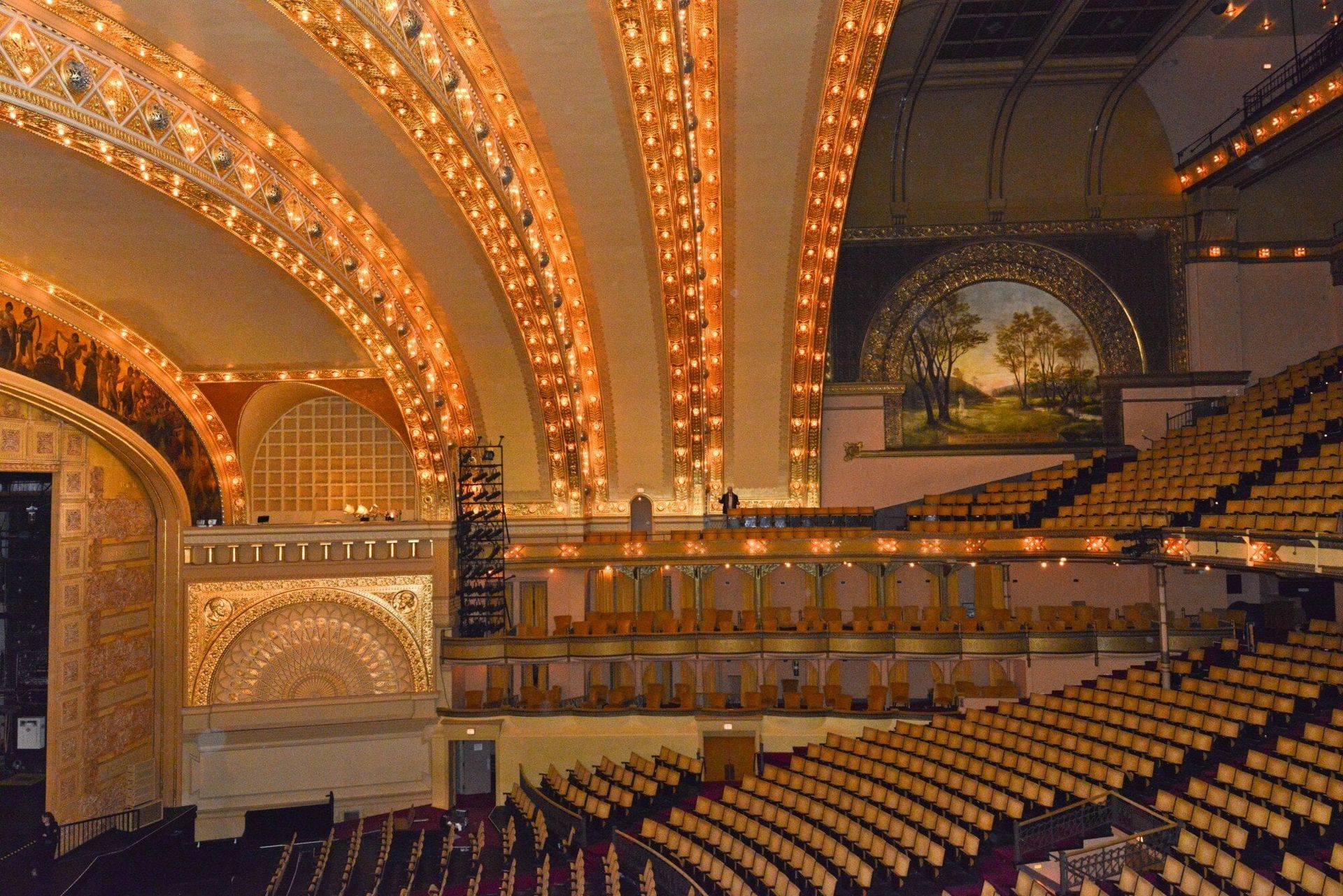

The Auditorium Building

The architecture firm Adler & Sullivan, founded in 1881 by Dankmar Adler and Louis Sullivan, stands as a key influence in Chicago's architectural history and the development of modern American architecture. Adler, an engineer and architect born in Germany, immigrated to the U.S. at age 10 and quickly excelled in both engineering and acoustics. Sullivan, an architect trained in Philadelphia and at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, became known for his bold ideas and adherence to the idea that “form follows function.” Together, they created a unique blend of structural innovation and decorative detail that became a precursor to modernist architecture.

Their partnership flourished as they applied pioneering engineering techniques, such as using steel frames to support larger, open spaces within their buildings. The Auditorium Building (1889) is perhaps their most famous work. Located on South Michigan Avenue, it is a combination of a theater, hotel, and office space. The structure showcased Adler’s expertise in acoustics, which made the theater one of the most celebrated in the nation, while Sullivan’s ornamentation added beauty and flair.

Beyond the Auditorium, the duo’s works included the Wainwright Building (1891) in St. Louis, one of the earliest modern skyscrapers. This building, with its ten-story height, was revolutionary for its time and is often considered one of the first “tall buildings” to embody Sullivan’s aesthetic ideas. Sullivan designed the façade with intricate organic motifs, marking a departure from the European-influenced architecture prevalent in American cities. Similarly, the Chicago Stock Exchange Building (1894) demonstrated both Adler's structural knowledge and Sullivan’s eye for lavish ornamentation, which was inspired by natural forms and fluid shapes.

Their partnership, however, was not without tension. Financial stressors in the 1890s, including the Panic of 1893, hit the firm hard. Adler increasingly focused on engineering projects to stabilize finances, leaving Sullivan feeling isolated in creative pursuits. In 1895, this strain ultimately led to their split. Adler joined another firm and continued smaller projects until his death in 1900, while Sullivan struggled to retain his influence without his business partner. Though he went on to design several smaller Midwestern banks and remain influential as a mentor to Frank Lloyd Wright, Sullivan's post-split career never reached the prominence he had achieved during his time with Adler. Despite his later financial struggles, Sullivan’s legacy as a visionary of modern architecture endures.