Humboldt Park

In 1869, a primarily German community on the city's west side petitioned to have a new park at North and California Avenues named after Alexander von Humboldt, a famous German scientist and explorer.

Humboldt Park boat house. Photo by Emily Barney, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 2.0.

Humboldt Park field house. Photo by Eric Wolf.

Humboldt Park boat house. Photo by Eric Wolf.

Humboldt Park. Photo by Emily Barney, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 2.0.

Humboldt Park boat house. Photo by Emily Barney, licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 2.0.

Official Name | Humboldt Park |

Address | 1400 N. Sacramento Ave. |

Architect | |

Neighborhood | Humboldt Park |

Current Use Type | |

Original Completion Date | 1869, 1907 |

Dedication day events for the new Humboldt Park were trilingual—said in German, Swedish and English—and drew in about 20,000 people. Humboldt never visited Chicago, but the use of his name can be credited to ethnic politics. When a statue of Humboldt was installed in 1892, the neighborhood was still heavily German and Scandinavian. Later, Polish immigrants moved in, resulting in the installation of an equestrian statue of political exile Thaddeus Kosciuszko at the park’s entrance, which was later moved to Solidarity Drive. The Polish were followed by a wave of Italian Americans and German and Russian Jews before Puerto Ricans began settling in the neighborhood in droves around the 1960s. Like the groups before them, the Puerto Ricans made their mark on the park, naming a road inside after Luis Muños Marín, Puerto Rico’s first elected governor.

Covering more than 200 acres, Humboldt Park was the biggest of three parks built by the West Park Commission. The Chicago & Pacific Railroad was persuaded to run adjacent to the property, creating the railroad suburb of Humboldt. Farther northeast, the town of Maplewood sprang up on another rail line. A boulevard connected the two points, with nodes named Logan Square and Palmer Square.

William Le Baron Jenney was appointed planner and landscape architect of all three of the West Park Commission’s parks: Humboldt, Douglas and Garfield parks. His concepts—winding, paved carriage drives, lagoons for drainage and carefully placed architectural elements—were influenced by his studies of landscape engineering in Paris, as well as by his working relationship with landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who he met during the Civil War. The park gave form to the flat topography and created interest that would encourage residential development. However, construction on the park was slow, and Jenney’s design can only been seen in about 80 acres in the northeast corner of the park.

JENNEY TO JENSEN

When neighborhood resident Jens Jensen became superintendent of the West Park system in 1895, Jenney’s work on the parks was superseded. Jensen’s interest in the Midwest environment, native plantings and the Progressive movement changed the way Chicagoans experienced parks. Humboldt Park was Jensen’s laboratory for his new ideas. By reshaping one of Jenney’s lagoons into a river, Jensen emphasized the natural prairie surrounding the city. Narrowing the water feature draws visitors through a variety of landscapes, including open meadows and varying densities of trees and shrubs, before finally culminating in multiple brooks lined with stone outcroppings. This feature changed over time, but it was reconnected with its past with a Chicago Park District restoration starting in 2004. Native wetland plants, prairie grasses and wildflowers, combined with recirculating water, were re-introduced. A wind turbine and solar panels provide the power for the water pumps. In a way, Jensen brought the country to the city for working class people who could not leave the city for the country.

ROSES AND RECREATION

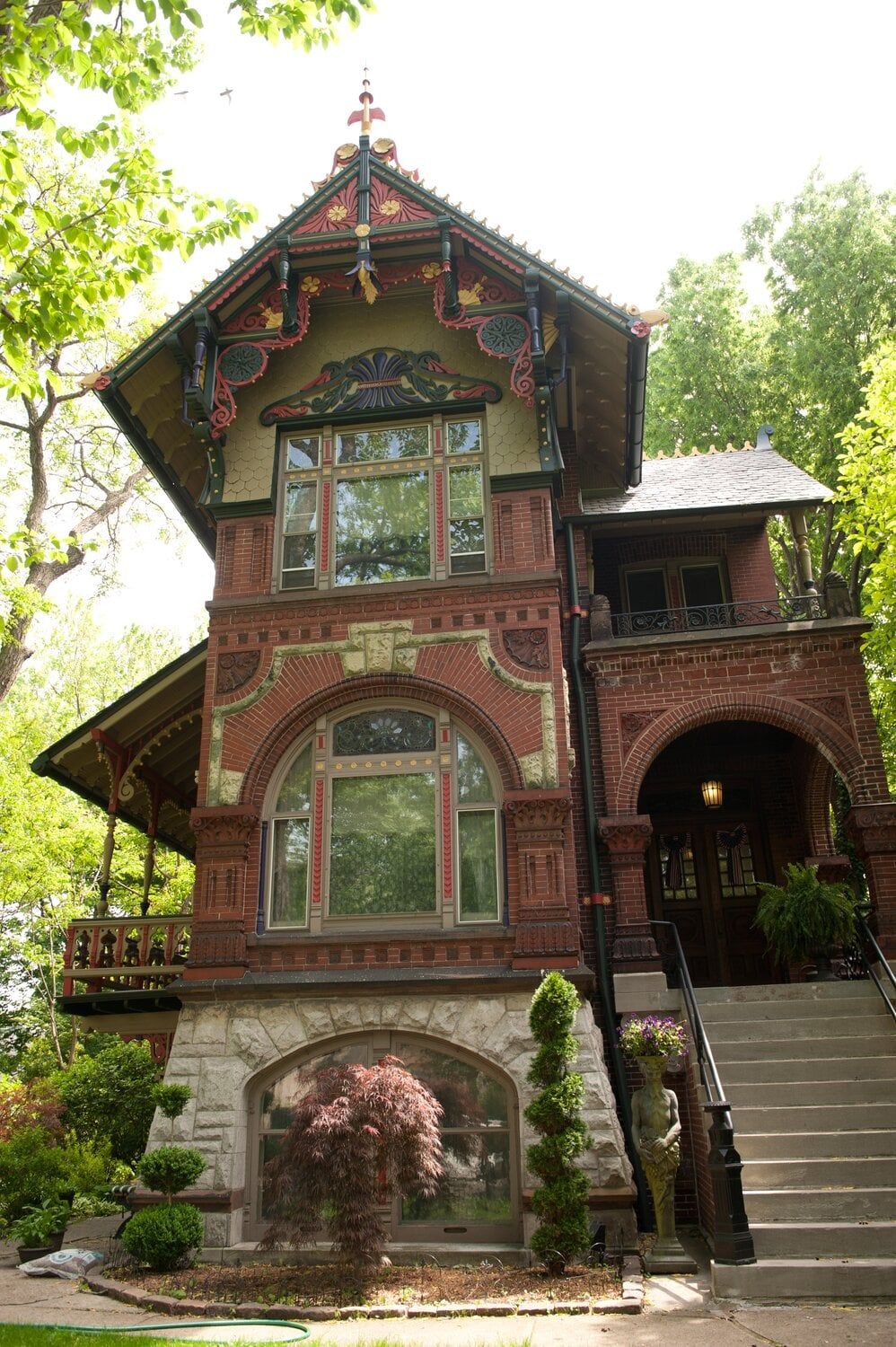

In 1895, stables designed by architects Frommann and Jebsen were built in Humboldt Park, at Division Street and Sacramento Avenue. The distinctive Queen Anne-style turrets stand out on the otherwise German-influenced building. In 1998, Harboe Architects restored the building, which now houses the National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts & Culture.

A sunken rose garden in Humboldt Park near Division Street was one of Jensen’s least favorite works; he called it “a folly of my youth.'” Today, however, it is a prominent and much loved component of the park’s landscape. A conservatory stood in the location until 1906, when it was replaced by the garden. In 1908, the garden was the site of a sculpture exhibition hosted by the Municipal Art League to educate the public to appreciate modern art. Adjacent to the garden was a hitching arena for carriages, where large terra cotta pots flanked a water fountain used by horses and people, common at the time.

In 1907, Jensen’s relationship with architects Schmidt, Garden and Martin brought their Prairie style boathouse to a park between the lagoon and since demolished music court. It offered majestic views of the pond and drew in visitors to the nearby band shell and amphitheater layout. Today the music court is a parking lot and the boathouse has been restored.

When the Prairie Style fell out of favor, a Georgian and English Tudor style fieldhouse designed by architects Michaelson and Rogstad was built. The 1928 structure is U-shaped with turrets on both ends. Today, it serves as a Chicago Park District gymnasium that faces a human-made beach.

HUMBOLDT'S FUTURE

And what happened to the railroad that served the town of Humboldt and the park? The tracks were raised to the top of a concrete structure in 1913. Recently, the tracks were converted into part of a new park called The 606, Chicago’s first elevated linear park. The 606 connects the neighborhoods of Humboldt Park, Logan Square, Wicker Park and Bucktown over a nearly three-mile route.

In addition, the Chicago Parks Foundation is leading a re-visioning of the 1908 Humboldt Park Formal Gardens, employing garden designer Piet Oudolf, of Lurie Garden fame.

For more than 140 years, the park and Humboldt neighborhood have gone through many cycles of urban change, including recent gentrification, but excellent examples of architectural and landscape design continue to grace the area.

Did you know?

Jens Jensen had a short commute. While serving as superintendent of the West Park system, he lived across the street from his office in the Humboldt Park stables. A parkway marker on Sacramento Boulevard, south of Division Street, honors him.

Did you know?

Two bison sculptures guard Humboldt Park’s formal garden, in the same way the lions guard the front of the Art Institute of Chicago. All the sculptures were created by Edward Kemeys.

Did you know?

A likeness of Norse-Icelandic explorer Leif Erikson honors the Norwegian community on the northwest end of the park.