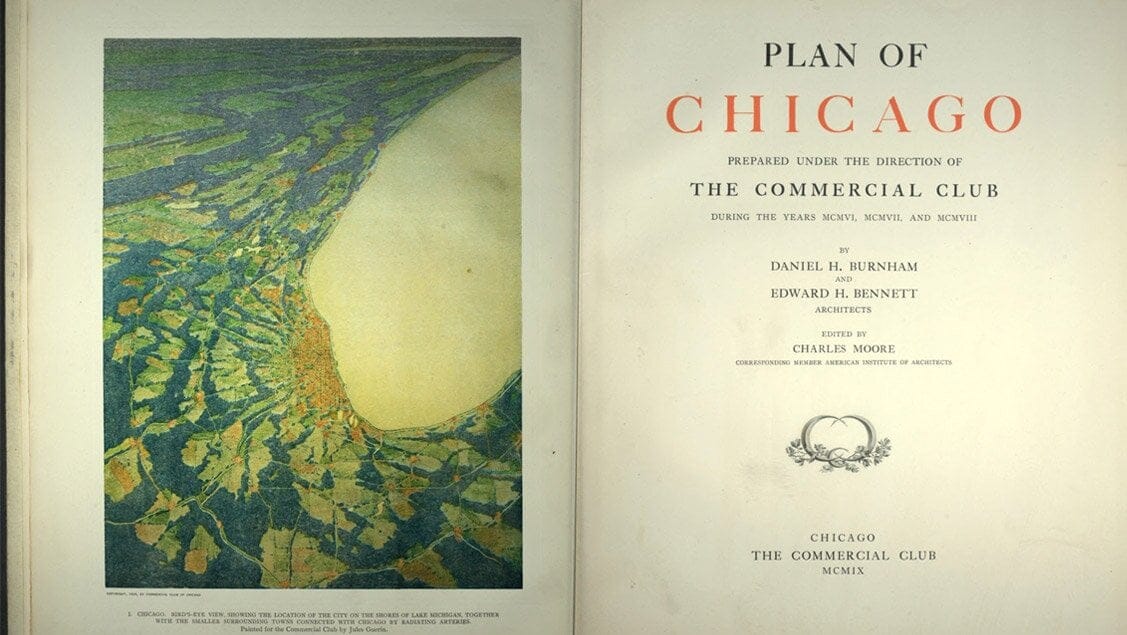

The 1909 Plan of Chicago, also commonly referred to as the “Burnham Plan,” was a visionary Progressive Era proposal that sought to beautify Chicago and improve efficiency of commerce. Published through the support of the Commercial Club of Chicago, the plan used renderings to convey the possible scenarios for a rapidly growing city. Although many of its aspirational ideas never became reality, as a document, the Plan of Chicago continues to serve as a reference in urban design today.

Beginning in 1906, a group of businessmen recognized the need to prepare a plan for Chicago’s growth and entrusted architect Daniel Burnham to develop a plan to address Chicago’s needs. Already famous for his role as Director of Works for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Daniel Burnham famously affirmed that Chicago should “make no little plans” for its future. He hired co-author Edward H. Bennett, then the two began their work.

Over the course of nearly three years, Burnham and Bennett researched numerous cities around the world. They studied how the growth of these cities and how large-scale infrastructure influenced the economy and mobility of their inhabitants. As a result, the Plan of Chicago was broken down into six categories and focused on the economic, transportation and social needs of Chicagoans.

The six categories, as laid out by Burnham and Bennett in the final chapter of the Plan of Chicago, are as follows:

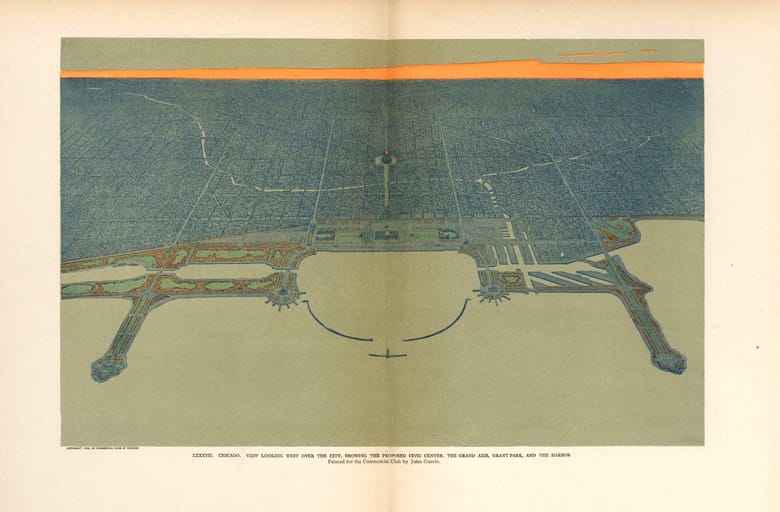

- The improvement of the lake front.

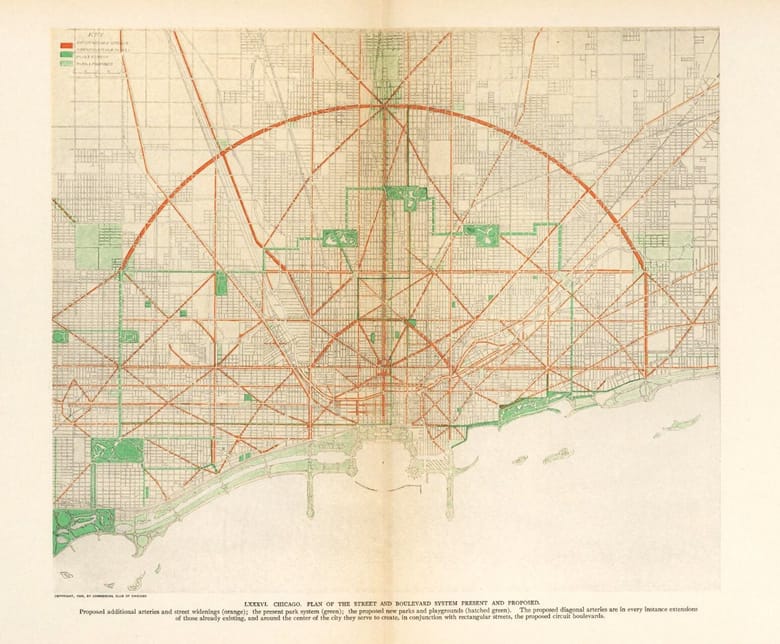

- The creation of a system of highways outside the city.

- The improvement of railway terminals, and the development of a complete traction system for both freight and passengers.

- The acquisition of an outer park system, and of parkway circuits.

- The systematic arrangement of the streets and avenues within the city, in order to facilitate the movement to and from the business district.

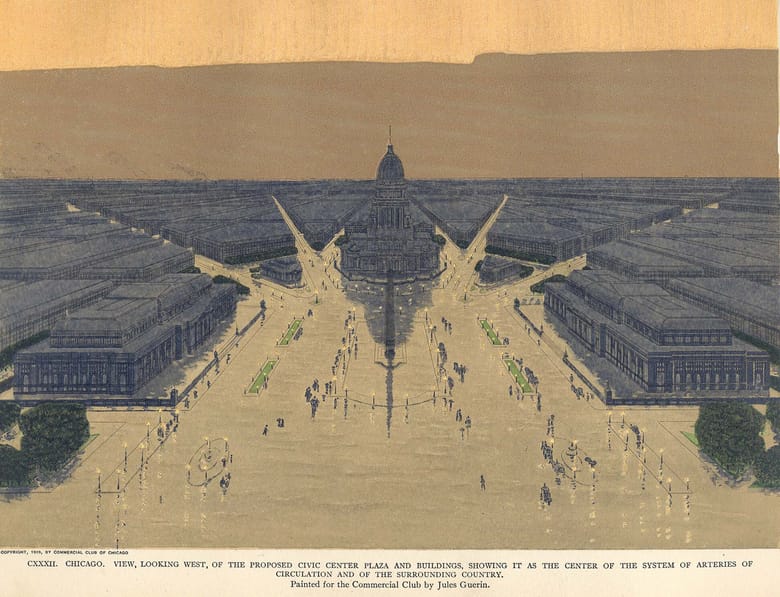

- The development of centers of intellectual life and of civic administration, so related as to give coherence and unity to the city.

While these principle design elements provided a plan for Chicago, Burnham and Bennett’s plan did not immediately change the city. The plan was presented to the City Council of Chicago in July 1909. The council created a planning commission by November of that year with Mayor Fred A. Busse appointing Charles H. Wacker as permanent chair of the commission. Projects such as the widening of Chicago’s streets and boulevards took shape over the next few decades. New streets were introduced, such as Wacker Drive along the Chicago River. One of the most noticeable portions of the plan to come to fruition is the city’s 25 miles of lakefront (out of its 29 miles of lakeshore) that serve as public parkland.

Although many of Burnham’s other initiatives were not directly implemented, the Plan of Chicago did have a profound impact on city planning. Burnham and Bennett wrote in its closing, “If, therefore, the plan is a good one, its adoption and realization will produce for us conditions in which business enterprises can be carried on with the utmost economy.” While the Plan of Chicago will never be fully realized, it continues to provide solutions and possibilities for the ever-changing Chicago—and for other cities around the globe.