How did the 1893 World’s Fair impact Chicago and its architecture?

WORLD, MEET CHICAGO

The World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 was the first world’s fair held in Chicago. Carving out some 600 acres of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Jackson Park, the exposition was a major milestone. Congress awarded Chicago the opportunity to host the fair over the other candidate cities of New York, Washington D.C. and St. Louis, Missouri. More than 150,000 people passed through the grounds each day during its six-month run, making it larger than all of the U.S. world’s fairs that preceded it.

The fair built awareness among visitors that Chicago was taking its place as the “second city” after New York. Locals, too, were proud of the enormous progress and growth that were achieved in the two decades following the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. So momentous was the fair that it is represented as a star on the Chicago flag.

How did the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition impact the architecture of Chicago? Most directly, the fair promoted the rapid urbanization of the South Side. New corridors of development grew along the lake and the new elevated “L” train line (today’s CTA Green Line) and new housing blocks were built for the fair’s workers. Entertainment venues and hotels sprung up in nearby Hyde Park and Woodlawn too, some of which would evolve into major resort destinations through the mid-20th century.

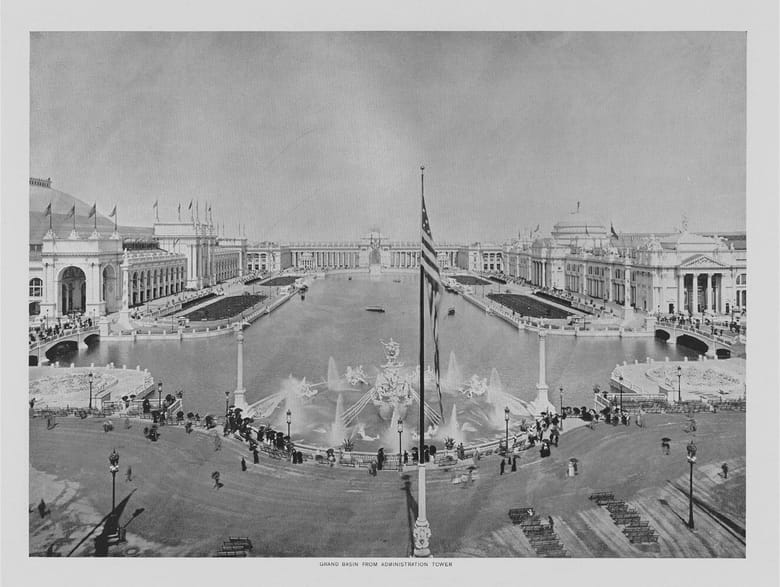

THE WHITE CITY

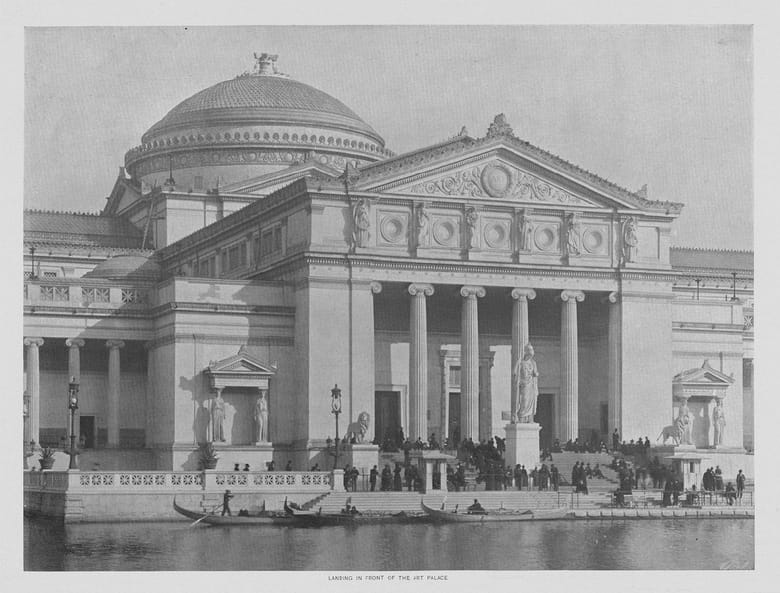

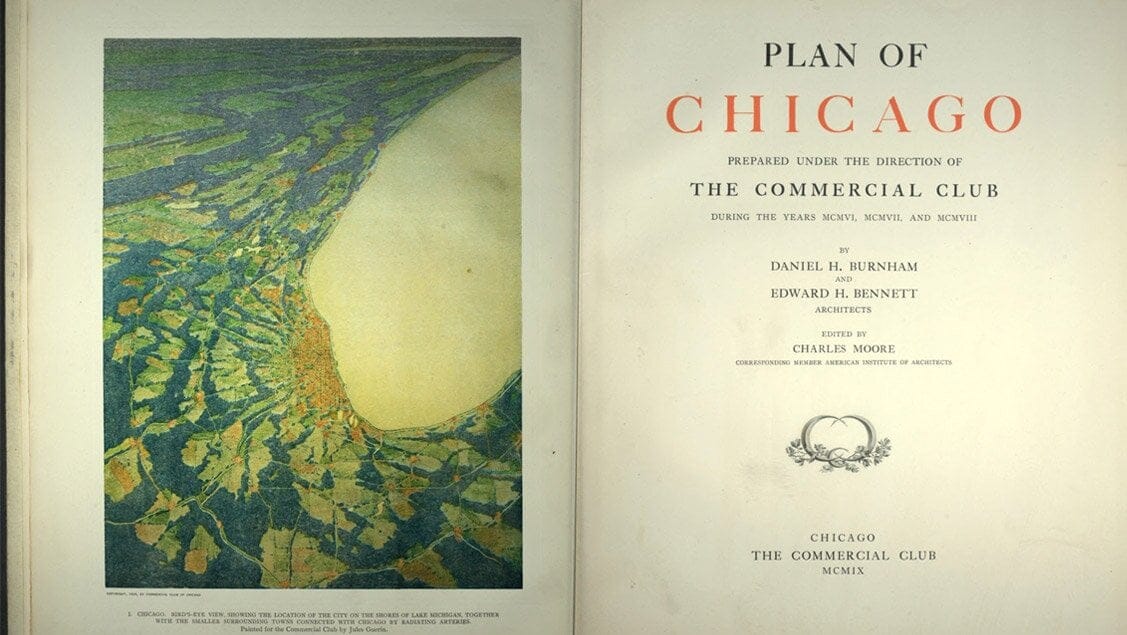

The site of the exposition itself gained the nickname the “White City” due to the appearance of its massive white buildings. The White City showcased chief architect Daniel Burnham’s ideas for a “City Beautiful” movement. While the fair’s buildings were not designed to be permanent structures, their architects used the grandeur and romance of Beaux-Arts classicism to legitimize the architecture of the pavilions and evoke solidity in this young city. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett’s 1909 Plan of Chicago was a culmination of lessons learned at the fair. The plan offered Chicago a blueprint for growth and influenced city planning around the world.

The grand Neo-Classical buildings of the White City—temples to industry and civilization—became templates for banks and public buildings across the country. They also influenced the designs of the museums that now stand on Chicago’s lakefront. The Museum of Science and Industry is housed in the former Palace of Fine Arts from the world’s fair. The Field Museum, which Burnham’s architecture firm helped plan, was the first occupant of the Palace of Fine Arts (in the 1920s, it moved to a different Neo-Classical building). The influence of the White City also extended to downtown, where the Art Institute of Chicago was built for the 1893 fair.

LEGACY OF THE FAIR

The millions of visitors who came to Chicago during the fair took home new ideas in commerce, industry, technology and entertainment. They crossed paths with others from around the world and walked away with a new perspective on Chicago. Travel writer James Fullarton Muirhead visited the fair from Scotland and later wrote: “Since 1893, Chicago ought never to be mentioned as ‘Porkopolis’ without a simultaneous reference to the fact that it was also the creator of the White City, with its Court of Honor, perhaps the most flawless and fairy-like creation, on a large scale, of man’s invention.”

Today, Chicago’s Beaux-Arts buildings serve as a reminder of the exposition. In fact, many Beaux-Arts buildings around the country owe their existence to the White City. A darker legacy lives on in the nonfiction book, The Devil in the White City. It follows Daniel Burnham’s work and the creation of the fair, as well as the actions of serial murderer Dr. H. H. Holmes. One of the fair’s most prolific physical legacies is the Ferris Wheel, which was invented in 1893 for the exposition’s amusements area on the Midway Plaisance. Thousands of “Chicago Wheels” now rise above cities around the world.